Welcome to "Bugs" & Human Health

Welcome to the “Bugs” and Human Health Webpage! We strive to ensure all of Virginia’s residents and visitors are safe by monitoring the diseases spread by mosquitoes, ticks, and a few of the other critters you might come across in your own backyards. On this site, you will find useful information to help keep you and your family protected and informed while exploring all of the beauty Virginia has to offer. Please take some time to browse through the various tabs across the top of this page and dive into the world of vector biology.

Prevention

Bites from mosquitoes and ticks can be both irritating and dangerous, as these insects serve as vectors for a number of diseases that affect humans. Luckily, there are many ways to protect and prevent yourself and your family against mosquito and tick bites.

Quick Links

-

Use EPA-registered Insect Repellent.

- When outdoors, use insect repellent containing either DEET, picaridin, IR 3535, 2-undecanone, or oil of lemon eucalyptus on skin or clothing. Always follow instructions on the product label.

- The insect repellent "permethrin" can also be used on clothing, shoes, bed nets, and camping gear and remain active after several washes. Be sure to apply it to clothing a few days before to allow for proper drying.

- You may still see ticks on clothing when using permethrin, but when used properly it will kill the ticks before they bite. It's a professional's go-to product when entering tick habitat.

-

APPLICATION FOR KIDS:

- Oil of lemon eucalyptus and para-menthane-diol should never be used for children under 3 years of age.

- Do not use insect repellent on babies under 2 months old.

- It is recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics to use products containing no greater than 30% DEET on children.

-

Wear loose-fitting, long-sleeved shirts and long pants in light colors.

- Mosquitoes are attracted to dark colors and wearing lighter colors will make it easier to spot a pesky tick on your clothing.

-

Tuck your pant legs into your socks for best practice tick avoidance.

- Most Virginia ticks live in the forest leaf litter and shady, grassy areas. Ticks do not climb high on vegetation or fly, so they must hitch a ride by climbing up your shoes or socks. Adhering to the fashionable practice of tucking pants legs into socks will help prevent ticks from climbing up your leg under your pants, and help you spot ticks before they can reach your skin. This also ensures the ticks get an effective dose of permethrin from your clothing.

-

Eliminate standing water on your property that can serve as mosquito breeding sites.

- Tip over and remove, or tightly cover, any containers that can hold water to prevent female mosquitoes from laying eggs.

- Places to think about include: old tires, buckets, planters, toys, pools, birdbaths, flowerpots, tarps, roof gutters and downspout screens, trash containers.

- If puddles or ditches cannot be drained or filled in, treat standing water with mosquito larvicides (dunks or granules) that can be purchased at most hardware stores.

- Other standing water issues can be directed based on their location:

- City or County Property – Call your city or county government about standing water on public property.

- State Roads – Call the Department of Transportation at 1-800-367-7623 about standing water along state roads.

- Storm Water Retention Ponds – Call the Department of Conservation and Recreation at 804-786-1712 or visit their website http://www.dcr.virginia.gov

- Tip over and remove, or tightly cover, any containers that can hold water to prevent female mosquitoes from laying eggs.

-

Keep mosquitoes out of the home.

- Install and utilize screens on doors and windows to reduce the chance mosquitoes will enter your home. Repairing any broken screens will also help to keep mosquitoes outside.

-

Check body and clothing for ticks after being outdoors

- Check clothing after spending time in tick habitats. Tumble dry clothing on high heat for 10 minutes to kill any remaining ticks.

- Use a mirror, friend, partner, or spouse to help check your body for ticks. Remember to check in armpits, in and around ears and hair, belly button, backs of knees, and between legs.

- Remember to inspect children, gear, and pets for ticks as well.

-

Use a tick prevention product for your dog as recommended by a veterinarian.

- Be sure to check your pet for ticks after outdoor activity as they may carry unwanted pests into the home.

-

How to properly remove a tick:

- Follow these steps:

- Use a tweezer to grasp the tick as close as possible to the skin.

- Pull upward, with steady even pressure, until the tick releases to avoid breaking the mouth-parts of the tick or rupturing the tick's body.

- After tick removal, clean the skin and bite area with rubbing alcohol or soap and warm water.

- *Save the tick in a bag or container with rubbing alcohol for identification in case an illness develops in the days after tick attachment. Never crush a tick with your fingers.

- Follow these steps:

Mosquito Prevention Video

Tick Prevention Video

"Bug" ID

In this section you will learn how to become an amateur entomologist (one who studies bugs). Your first lesson is in regards to the word “bug”, which actually refers to a specific category and name of insect within the animal kingdom. Even so, we’re with you in that it’s much easier to refer to all creepy crawlies as “bugs”. Scroll on through to see if you might have found an important “bug” of public health concern.

Quick Links

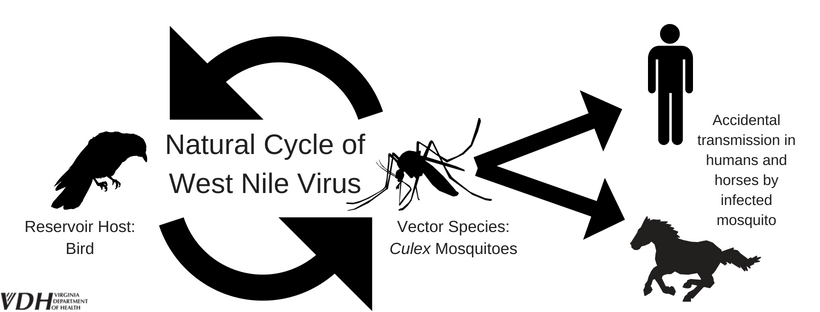

Ticks

The American Dog Tick is relatively evenly distributed throughout Virginia and is an important vector for diseases that affect humans and pets. The adult females can be identified by their off-white and patterned scutum, or “shield” just behind their head on the backside, and dark brown body.

Risk Characteristics:

The adult female American dog tick is the primary vector stage of this tick known to transmit disease to people. Adults are most active early spring and mid-summer. American dog ticks prefer sunny and open areas with less tree cover such as edges of trails, fields with medium-height grass, or shrubby overgrown areas.

Potential Vector for:

Rocky Mountain spotted fever, tularemia, Rickettsia parkeri, and tick paralysis (in dogs and humans; usually diminishes upon tick removal)

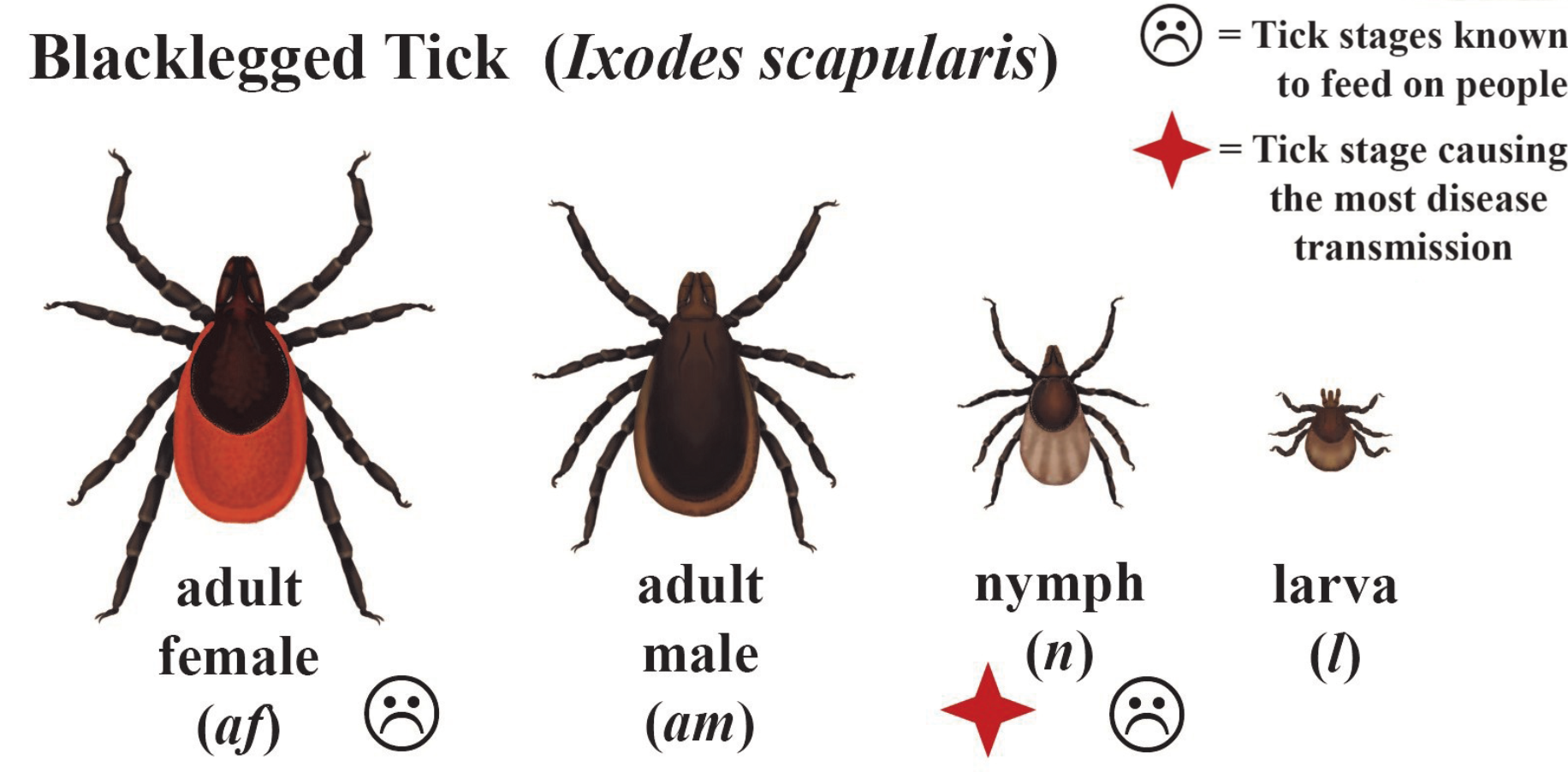

The Blacklegged tick, often called the deer tick, is a tick of major public health importance in Virginia and the Eastern US. The male ticks are dark brown or black in color and resemble a watermelon seed. The females are red-brown behind their scutum, or shield just behind their head on the backside.

Risk Characteristics:

The nymphal stage of the Blacklegged tick is the main vector for transmitting disease to people. This stage is most active during late spring and early summer. Adults have been known to bite people much less frequently but still pose a risk for disease transmission on early spring, fall, and even the warmer winter days. Blacklegged ticks may prefer to inhabit higher elevations, above 1,600 ft. and prefer leaf litter or shaded vegetation on forest floor.

Potential Vector For:

Lyme, Borrelia miyamotoi, Anaplasmosis, Powassan virus, and Babesiosis

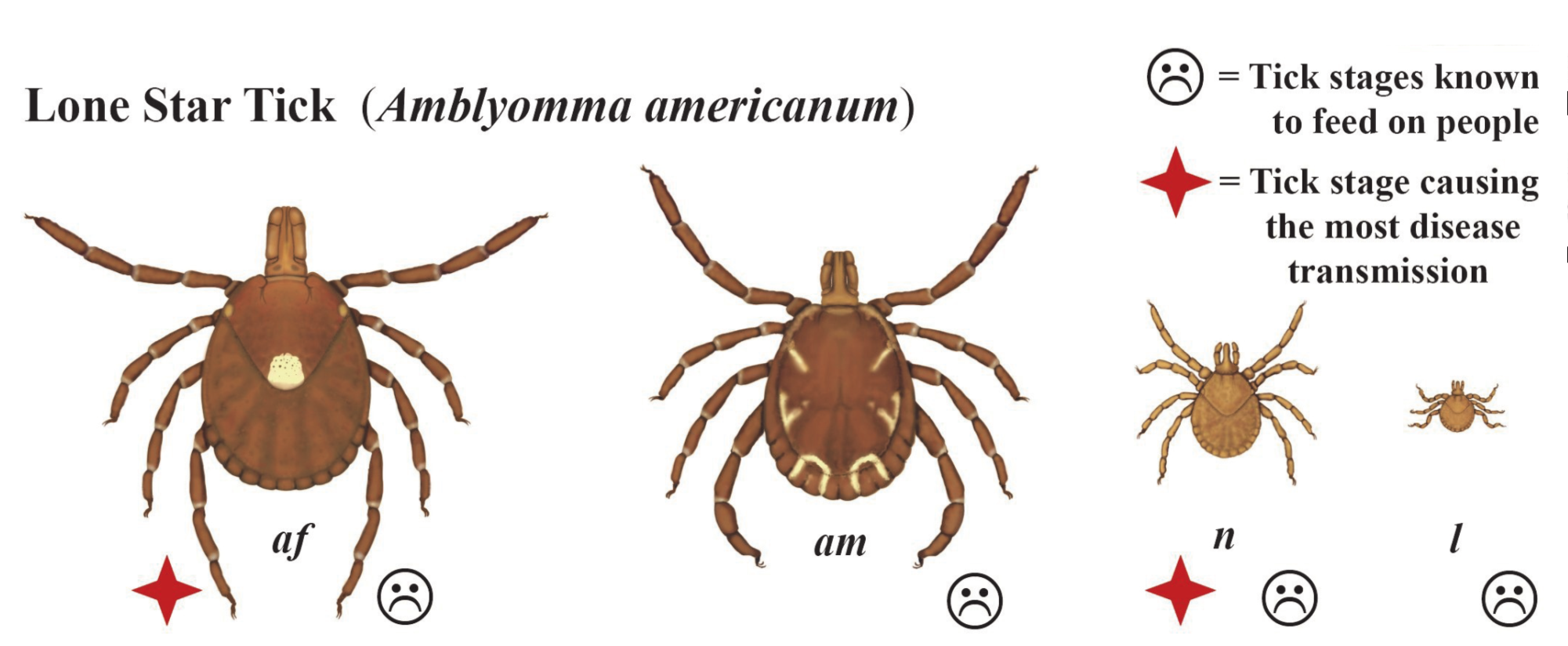

The Lone star tick is widely distributed throughout Virginia but tends to prefer areas below 1,600 ft. in elevation. This tick is an aggressive biter and has the potential to transmit serious diseases. The adult female is best recognized by a white dot, or “lone star”, on the center of her back.

Risk Characteristics:

The adult female and the nymph stage most frequently transmit disease to humans. The nymph stage is active from spring through mid-summer while the adults are most active late winter to early summer. The Lone star tick is often found in leaf litter on the forest floor or in partly shaded grass. In Virginia, the highest concentrations of Lone star ticks have been collected around the Eastern Piedmont and Coastal Plain regions.

Potential Vector For:

Ehrlichiosis, Tularemia, Southern-Tick Associated Rash Illness (STARI), Heartland Virus Disease, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, R. parkeri, and Alpha-gal allergy

The Longhorn tick (also known as a Bush Tick or Cattle Tick) is native to East Asia and has only recently [May 2017] been identified in the United States. It is unknown how long this tick has been present in the US, as archived ticks from an infestation in 2011 have been retrospectively determined as H. longicornis.

Risk Characteristics:

Little is known about the longhorn tick as an invasive species in the United States due to their relatively recent discovery. Generally, the longhorn tick preferentially feed on livestock animals, wildlife, and domestic animals. However, reports of longhorn ticks parasitizing on humans in the US has elicited increased attention from public health agencies. Of note, this tick can reproduce asexually so it may be present at all stages at all times of the year.

Potential Vector For:

*speculated based on capabilities in native population, the invasive Longhorn Tick has yet to be determined as a competent vector for any of the following conditions*

Anaplasma, Ehrlichia, Lyme, Cattle theileriosis (in cattle), Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome, and Powassan Virus

Mosquitoes

The Asian tiger mosquito is the most common and widespread pest mosquito in Virginia. These mosquitoes have distinctive black and white banding on their legs.

Risk Characteristics:

Asian tiger mosquitoes are primarily day-time biters. They will only breed or lay their eggs in water holding containers or tree holes. They also tend to aim for ankles, legs, and backs or undersides of arms when people are standing relatively still, or moving slowly. They are most active during mosquito season, May to October.

Therefore, the best way to prevent an Asian tiger mosquito bite is to remove any water-holding containers in your yard that could host mosquito larvae and remain extra vigilant when outdoor during daylight hours, applying insect repellant with careful attention to the areas listed above.

Potential Vector For:

Chikungunya, Dengue, Yellow Fever, West Nile virus, La Crosse encephalitis, and Zika

This important vector species will readily enter homes and buildings to bite humans, but prefer to get their blood meal from birds when outdoors. In Virginia, they serve as the most important vector of West Nile virus. This mosquito boasts a golden brown body, likely indistinctive to the untrained eye.

Risk Characteristics:

Culex pipiens is known to be an active biter in the evening or early morning hours. These mosquitoes also lay eggs in water holding containers such as flower pots or bird baths and puddles, stagnant ditches, storm drains, or neglected pools. They particularly prefer polluted water that is rich with organic material (leaves, dirt, sewage, etc.). They are most active during mosquito season, May to October.

Based on their behavior, the best way to prevent a bite from a Northern house mosquito is to tip over and eliminate standing water in your yard. Fill ditches and puddles or purchase mosquito larvicide dunks or bits from your local hardware store to treat water you can't eliminate. Use repellent during outdoor evening activities and ensure screens on windows and doors are intact.

Potential Vector For:

West Nile Virus, St. Louis Encephalitis, and Heartworm parasite (to domestic animals)

Other "Bugs"

No one wants to find bed bugs hiding in homes or hotels. While these bugs can cause itchy rashes and pose serious challenges to remove, they do not transmit or spread disease.

Adult bed bugs are about the size and shape of an apple seed. Younger nymphs are typically more difficult to spot due to their translucent color and smaller size. Bed bug eggs may be nearly impossible to spot at about 1mm in size. For more information visit EPA’s or Division of Environmental Health's Bed Bug Resource.

Risk Characteristics:

Bed bugs like to hide in the seams and folds on fabric as well as in electrical sockets, drawer joints, and loose wallpaper. Always check in these areas if you suspect bed bugs. In your home, you can prevent bed bugs by reducing clutter, keeping carpet and furniture clean and vacuumed, and sealing cracks and crevices.

Potential Vector For:

A bed bug bite can create an itchy and irritating rash but they are not known to transmit or spread any diseases.

There are more than 30 spider species in Virginia. Most spider species in Virginia are not aggressive or dangerous and will not bite unless tampered with. However, a bite from either the black widow spider or the brown recluse spiders could both require medical attention. To learn more about spiders in Virginia, click here.

Tick-borne

Here in Virginia, it doesn’t take long to come across a tick crawling up your pant leg after spending some time in or around a wooded area. In this section we have provided an overview of the ticks commonly found in Virginia and that you would be likely to encounter on your outdoor adventure as well as some of the diseases they could potentially be carrying. When planning any outdoor activities you should use the instructions found under the “Prevention” tab to reduce your risk of being bitten.

Tick-borne Diseases & Conditions

Alpha-gal syndrome, or acquired red meat allergy, is a tick-acquired red meat allergy associated with the bite of a lone star tick. The allergy involves a carbohydrate known as galactose-alpha-1, 3-galactose. This carbohydrate is regularly found in mammalian meats such as beef, pork, venison, and lamb. For some individuals the allergy is limited to meats high in fat like beef, but for others, protein powders, dairy products, gelatin, and even the cancer drug Cetuximab can cause an allergic reaction.

Transmission:

Some individuals exposed to the bite of a lone star tick may be at risk for this acquired allergy. The alpha-gal carbohydrate is found in the tick’s saliva and injected into an individual’s skin when the tick feeds. The tick’s saliva prompts an immune response from the human body to develop antibodies in an attempt to combat the foreign substance. However, now the immune system has a difficult time determining whether or not the alpha-gal carbohydrate floating around in your blood is from the tick or from the burger you just ate, potentially resulting in an allergic reaction.

Symptoms:

As with most allergies, there are a multitude of symptoms that might arise depending on the individual’s own immune response. The allergy can manifest in hives, angiodema (swelling of the skin and tissue), upset stomach, diarrhea, stuffy or runny nose, sneezing, headaches, a drop in blood pressure, and in certain individuals, anaphylaxis can result.

Symptoms usually appear approximately 4-8 hours after ingesting red meat. In some individuals the allergy will diminish with time, particularly if there are no further exposures to lone star ticks. It would be wise to slowly reintroduce red meats to your diet if you’ve had a known red meat allergy or to avoid them altogether. It’s hard to say how long one might maintain the acquired red meat allergy, as this syndrome is still being researched.

Laboratory testing:

A physician or allergist is able to diagnose acquired red meat allergy by performing blood tests.

Statistics:

It is unknown how many cases occur on a yearly basis in Virginia as the syndrome is not currently on the reportable diseases list.

For more information see Acquired Red Meat Allergy

Anaplasmosis is caused by the bacterial agent Anaplasma phagocytophilum and is transmitted to humans via the bite of an infected black-legged (Ixodes scapularis) tick.

Transmission:

The most likely method of transmission is through the bite of an infected black-legged tick, but in rare cases, Anaplasma phagocytophilum has been spread by blood transfusion. Otherwise, it cannot be transmitted directly from person-to-person.

Symptoms:

Symptoms will typically begin within 1-2 weeks after the bite of an infected tick. Early signs usually present as an acute onset of fever, headaches, body aches, nausea, vomiting, and in rare cases, a rash. Also characteristic of the illness are signs such as leukopenia (low white blood cell count), thrombocytopenia (low platelet levels), elevated liver enzymes, and anemia.

Laboratory Testing:

Testing for Anaplasmosis usually consists of serological testing for antibodies present in the blood. Anaplasmosis is serologically cross-reactive with Ehrlichiosis, which causes added laboratory challenges. To determine a current, ongoing infection, it may be necessary to provide an acute serum sample paired with a second sample taken about a week or so after the first. This paired sample method allows us to observe a change in the amount of antibody present in the blood when comparing the first and second serum samples. However, the preferred method of testing is PCR of whole blood (usually Multiplex PCR, which is able to detect multiple challenges at once), to confirm the presence of Anaplasma phagocytophilum in an individual’s blood.

Treatment:

Treatment with the antibiotic (doxycycline) is the only effective treatment for Anaplasmosis.

Statistics:

The incidence of Anaplasmosis in Virginia has been increasing in recent years. There have been an average of 13 cases of reported Anaplasma phagocytophilum per year, and 18 cases on average if you include those that go undetermined as either anaplasmosis or ehrliciosis due to serological cross-reactivity among testing mechanisms.

For more information see Anaplasmosis

Babesiosis is caused by a couple different parasites of the Babesia genus. There is Babesia divergens and Babesia duncani, but their vectors are not found here in Virginia and should not be considered as a cause of illness unless the individual has had recent relevent travel. The causative agent and culprit in Virginia Babesia cases is Babesia microti.

Transmission:

Humans become infected with the Babesia microbe via the bite of an infected Blacklegged tick. Human-to-human transmission does not occur except in the case of blood transfusions which have been documented in the past.

Symptoms:

Most individuals who become infected with Babesia do not exhibit symptoms of disease. Others will develop flu-like, non-specific symptoms such as fever, chills, sweats, headache, body aches, nausea, loss of appetite, and fatigue. Babesia is well known for infecting red blood cells and can cause a specific form of anemia called hemolytic anemia that can result in jaundice (yellowing of the skin) and dark urine. Other characteristic signs of babesiosis include a low and unstable blood pressure, low platelet count, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC – which can lead to blood clots and bleeding), malfunction of vital organs, and in severe cases death may result.

Laboratory Testing:

Lab testing for babesiosis involves the identification of the Babesia parasite in a blood smear under the microscope or detection of the organism’s DNA in whole blood using PCR methods.

Treatment:

Treatment of babesiosis usually involves the combination of two prescription medications: an antibiotic and an antiparasitic, taken together over a 7-10 day period. In more severe cases, additional supportive care may be necessary.

Statistics:

There have been 10 total cases of Babesiosis reported within the last decade in Virginia.

For more information see Babesiosis

Bourbon virus is a novel condition first detected in 2014. Research on this virus is still ongoing but it is believed to be a severe, tick-borne illness with a similar transmission cycle to Heartland virus.

Transmission:

It is currently hypothesized that people acquire Bourbon virus through the bite of an infected Lone Star tick.

Symptoms:

Due to a limited number of identified cases, little is known about the typical presentation of Bourbon virus. People with confirmed cases of Bourbon virus have had fever, fatigue, headache, joint aches, nausea, vomiting, and rash. People have also reported leukopenia (low white blood cell count) and thrombocytopenia (low platelet count).

Laboratory Testing:

No commercially available testing currently exists for Bourbon virus and laboratories are currently developing specific testing mechanisms to indicate Bourbon virus infection. The CDC has the capacity to test specimen if a case of Bourbon virus is suspected.

Treatment:

Antibiotics are not an effective treatment as this condition is a virus. While no specific treatment exists, patients with Bourbon virus may require hospitalization and supportive care to manage symptoms.

Statistics:

Bourbon virus is not currently a notifiable disease so statistics for case numbers in Virginia are unknown. Since its identification in Bourbon County, Kansas in 2014, a limited number of cases have been identified in Missouri, Oklahoma, and other neighboring states.

Two rickettsial bacteria species of ehrlichiosis are currently known to infect humans and cause illness; Ehrlichia chaffeensis and Ehrlichia ewingii.

Transmission:

The bacteria are transmitted to humans by the bite of an infected lone star ticks. Ehrlichiosis cannot be transmitted from person-to-person, except by blood transfusion. Lone star ticks are the most common tick to bite people in Virginia, and as many as 1 in 20 lone star ticks (5%) may be infected with an Ehrlichial agent.

Symptoms:

Ehrlichiosis cases range from mild to moderately severe, with a few cases causing life-threatening or fatal illness. Infected individuals that experience symptoms may expect a fever and one or more of the following; headache, chills, discomfort, muscle pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, confusion, and a rash or red eyes that begin about one to two weeks after the bite of an infected tick. Ehrlichiosis causes rash in about 30% of infected adults and 60% of infected children. Severe cases may cause difficult breathing, neurologic problems, and bleeding disorders. Symptoms and biological markers of Ehrlichiosis may be similar to those of Anaplasmosis and RMSF, causing those illnesses to also be considered as well in the diagnosis.

Laboratory Testing:

There are multiple ways to test for Ehrlichiosis, one of which is a method called indirect immunofluorescence IgG assay that detects Ehrlichiosis specific markers. This test involves a blood sample taken as early as possible and a second blood sample taken 2 to 4 weeks later to compare immunological response. The best laboratory method to assist in diagnosis of Ehrlichiosis is the Multiplex PCR which can detect the DNA of multiple pathogens at one time.

Treatment:

Prompt treatment (in the first five days of illness) with an appropriate antibiotic (doxycycline) will minimize the chances of a severe illness development, and usually results in a rapidly effective cure. Ehrlichiosis can be a severe or fatal illness, so treatment should be given based on suspicion of illness, and not be delayed until laboratory results are complete.

Statistics:

On average, there have been 95 cases of ehrlichiosis or undistinguished ehrlichiosis/anaplasmosis cases per year in Virginia within the last decade.

For more information see Ehrlichiosis

Heartland virus, first identified in Missouri in 2009, has been described as a phlebovirus that can infect humans after the bite of an infected Lone Star tick.

Transmission:

It is currently believed that people acquire Heartland virus through the bite of an infected Lone Star tick.

Symptoms:

People infected with Heartland virus may experience symptoms such as fever, fatigue, headache, nausea, joint aches, and diarrhea. Incubation time, or time from tick exposure to illness onset, is estimated to be about 14 days.

Laboratory Testing:

No commercially availble testing currently exists for Heartland virus. However, patients with symptoms and exposure consistent with Heartland virus may be tested for evidence of viral antibodies at CDC arboviral rickettsial diseases branch upon clinician request.

Treatment:

Many patients infected with Heartland require hospitalization, with most patients having full recovery after supportive care and intravenous fluids.

Statistics:

Heartland virus is not currently a notifiable disease so statistics for case numbers in Virginia are unknown. Since its identification in 2009, about 30 cases have been reported from the Midwest and Southeast US.

Lyme Disease is caused by the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi and spread to humans by the bite of an infected Blacklegged tick.

Transmission:

The bacteria that causes Lyme disease is only transmitted through the bites of infected blacklegged ticks (also called deer ticks). The tiny blacklegged tick nymphs cause most cases of infection. The black legged nymph season takes place in early summer, coinciding with peak outdoor human activities (sports, hiking, etc.). Since blacklegged nymphs are very small, move slowly, and tend to cause little itch or irritation compared to other Virginia ticks, most people never realize they have been bitten unless the tick attaches to a part of the body that is in plain sight. Lyme disease is not transmitted person-to-person.

Symptoms:

Most patients (about 75%) will see the development of a red rash called an erythema migrans (“EM” or “bull’s-eye” rash) around a tick bite site within days or weeks of the tick bite. This rash expands (up to 12 inches in diameter) and often clears around the center. The rash does not itch or hurt, so it may not be noticed if it is on a person’s back-side or scalp. The initial illness may cause fatigue, fever, headache, muscle and joint pains, and swollen lymph nodes.

If untreated or improperly treated in the early stage of illness, some patients may develop one or several of the following symptoms: multiple EM rashes on their body, intermittent arthritis (pain and swelling) in their large joints (e.g., knees), facial palsy, heart palpitations, severe headaches/neck stiffness (due to inflammation of spinal cord), or neurological problems (shooting pains or numbness and tingling in hands and feet, or memory problems) months to years after the initial illness. Pain and swelling in large joints will occur in about 60% of untreated patients and neurological symptoms occur in about 5% of untreated patients. Arthritis and neurological problems may last for years after the infection.

Laboratory testing:

The diagnosis of Lyme disease is based primarily on signs and symptoms of illness. Laboratory tests for Lyme disease antibody may be done on a patient’s blood to confirm the diagnosis, but if blood is collected too early in the course of illness, an infected person may not yield an antibody response. If laboratory confirmation is desired, re-testing may be necessary.

Treatment:

When Lyme disease is detected early and treated with an appropriate antibiotic (e.g., doxycycline), treatment is typically effective.

Statistics:

The number of reported Lyme disease cases have been dramatically on the rise in recent years. 2017 had the highest ever number of Lyme disease cases in VA with 1,652 reported cases. On average, 1,215 cases have been reported per year in VA during the last decade. Lyme disease may also be heavily under-reported with a CDC study estimating that only 30,000 cases are reported from 300,000 cases annually.

For more information see Lyme Disease

Powassan Virus (POW) is a flavivirus that can be transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected Blacklegged tick.

Transmission:

People acquire POW virus through the bite of an infected Blacklegged tick. The virus can be transmitted in as little as 15 minutes, much faster than most other tick-borne illnesses found in Virginia. Powassan virus is typically maintained in a cycle amongst ticks and small-to-medium-sized rodents that they feed on, such as woodchucks, squirrels, and white-footed mice to name a few. There are two separate types of POW virus in the U.S. (POW1 and POW2). POW1 virus is transmitted by the ticks that feed on woodchucks and squirrels. POW2 virus is transmitted by the black-legged tick, the same tick responsible for Lyme disease transmission in Virginia.

Symptoms:

Most individuals do not experience symptoms. However, those that do may notice symptoms such as fever, headaches, vomiting, general weakness, confusion, loss of coordination, speech difficulties, or seizures appearing within 1 week to 1 month of suspected tick bite. About half of the survivors of POW experience permanent neurological symptoms.

Laboratory Testing:

Laboratory diagnosis generally involves testing of serum or Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) to detect virus specific IgM and neutralizing antibodies. Initial serological testing will be performed using IgM capture ELISA, MIA (Microsphere-Based Immunoassay) and IgG ELISA. If the initial results are positive, further confirmatory testing may delay the reporting of final results.

Treatment:

Currently there are no vaccines or medications developed to treat or prevent POW virus infection. Persons with severe POW illnesses often need to be hospitalized, where they can receive respiratory support, intravenous fluids, and medications that decrease swelling in the brain. After illness, recovery may require long-term therapy to regain speech and/or movement of limbs.

Statistics:

There has been only one reported case of Powassan virus infection in the state of Virginia (in 2009).

Rickettsia parkeri is a tick-borne bacterial disease belonging to the Spotted Fever Rickettsial group (SFR).

Transmission:

SFR is spread by the bite of an infected tick, or by contamination of the skin with tick blood or feces. It cannot be spread from one person to another. Usually, ticks must be attached to the person for a period of between ten and twenty hours in order for transmission to occur, but there have been instances of SFR transmission in which ticks were attached for less than an hour.

Symptoms:

Symptoms usually appear within two weeks of the bite of an infected tick. R. parkeri disease is typically less severe than the other major disease of the SFR group with symptoms including fever, headache, muscle aches, and rash. People diagnosed with this illness typically have an eschar (dark scab) at the tick bite location.

Laboratory Testing:

SFR can be diagnosed through laboratory tests of blood or skin. If an eschar is present, it can be used to accurately diagnose R. parkeri disease. Antibodies to the infectious agent typically do not become detectable until seven to ten days after onset of illness, therefore testing for the agent’s DNA via PCR is the best diagnostic laboratory test in the early stages of illness.

Treatment:

Rickettsial infections can be treated with certain antibiotics in both children and adults. Prompt treatment may decrease the chance of developing serious illness.

Statistics:

R. parkeri is reported within the Spotted Fever Rickettsial group which includes RMSF. In the last decade, there have been an average of 255 SFR cases in Virginia per year.

For more information see Spotted Fever Rickettsiosis

Rickettsia rickettsii is a tick-borne bacterial disease belonging in the Spotted fever Rickettsial group (SFR).

Transmission:

SFR is spread by the bite of an infected tick, or by contamination of the skin with tick blood or feces. It cannot be spread from one person to another. Typically, ticks must be attached to the person for a period of between ten and twenty hours in order for transmission to occur, but there have been instances of SFR transmission where ticks were attached for less than an hour.

Symptoms:

Rocky Mountain spotted fever(RMSF) is characterized by a sudden onset of moderate to high fever, severe headache, fatigue, deep muscle pain, chills and rash. The rash typically begins on the legs or arms, may include the soles of the feet or palms of the hands, and may spread rapidly to the trunk or rest of the body. If left untreated Rocky Mountain spotted fever can be fatal.

Laboratory Testing:

SFR can be diagnosed through laboratory tests of blood or skin. Antibodies to the infectious agent typically do not become detectable until seven to ten days after onset of illness, therefore testing for the agent’s DNA via PCR is the best diagnostic laboratory test in the early stages of illness. If PCR is not preformed, the pairing of an acute and convalescent serum sample taken seven or so days apart can be an effective means of diagnosing RMSF.

Treatment:

Rickettsial infections can be treated with certain antibiotics in both children and adults. Prompt treatment may decrease the chance of developing serious illness.

Statistics:

RMSF cases are reported within the Spotted Fever Rickettsial group which also includes R. parkerii. In the last decade, there have been an average of 255 SFR cases in Virginia per year.

For more information see Spotted Fever Rickettsiosis

Francisella tularensis is the bacterial pathogen that causes Tularemia. While rare in natural occurrence, Tularemia is of major public health concern and is listed as a category A bioterrorism agent for its historic role in biological weapon research.

Transmission:

Tularemia cannot be spread from one person to another, but can be spread in a variety of other ways. The skin, eyes, mouth and throat of hunters may be exposed to the bacteria while skinning or dressing wild animals, especially rabbits or hares. Handling or eating uncooked meat from infected animals, handling pelts and paws of animals, drinking contaminated water, or getting bitten by certain arthropods may also transmit the bacterial disease. Another possible, but rare, route of exposure is by inhaling infected aerosols, such as dust from contaminated soil, hay or grain.

Symptoms:

Symptoms typically appear 3 to 5 days after exposure to the bacteria, but can take anywhere between 1 to 14 days to develop. Tularemia causes different symptoms depending on where and how the bacteria has entered the body. Tularemia can cause swollen and painful lymph glands, inflamed eyes, sore throat, ulcers in the mouth or on the skin, and pneumonia-like illness. Early symptoms almost always include the abrupt onset of fever, chills, headache, muscle aches, joint pain, dry cough and progressive weakness. Pneumonia may be a complication of infection and requires prompt diagnosis and specific treatment to prevent death.

Laboratory Testing/Diagnosis:

Tularemia can be difficult to diagnose. It is a rare disease, and the symptoms can be mistaken for other more common illnesses. For this reason, it is important to share with your health care provider any likely exposures, such as tick and deer fly bites, or contact with sick or dead animals. Laboratory tests of specimens taken from the affected part(s) of the body can help confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment:

Early treatment with an antibiotic is recommended.

Statistics:

Tularemia occurs very infrequently in Virginia where there has been an average of 2 cases per year in the last decade.

For more information see Tularemia

Mosquito-borne

Mosquito season ranges from early May to to late October/early November. Most people have had the experience of being pestered by mosquitoes while trying to enjoy a cookout, pool party, or some other outdoor activity. It may be hard to believe, but we have about 60 different kinds of mosquitoes here in Virginia, each with their own particular habitats and behaviors. This poses a challenge to controlling their level of nuisance around the areas we call home. The best method of keeping mosquitoes at bay is through community collaboration and remembering to “Tip, Toss, and Cover” any water holding containers on your property at least once a week. Together, we can reduce the risk of mosquito-borne disease in Virginia.

Locally Acquired Mosquito-borne Diseases

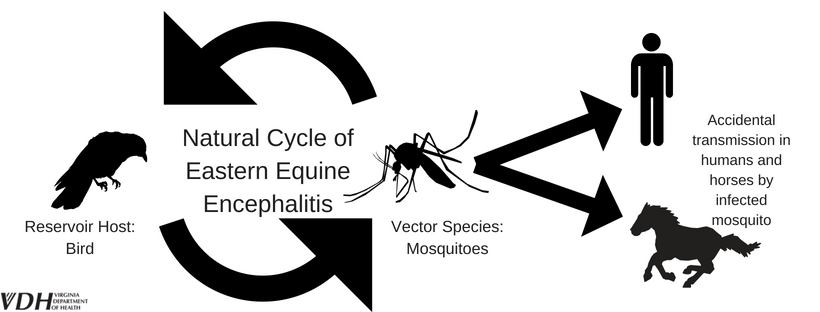

Eastern equine encephalitis virus (EEEV) is naturally maintained in a cycle between wild birds and Black tailed (Culiseta melanura) mosquitoes. These mosquitoes are primarily associated with freshwater swamp-forests and coastal areas in Virginia. Humans and horses are considered "dead end" hosts because they do not develop enough virus in their bloodstream to reinfect mosquitoes and continue the transmission cycle.

Transmission

An infected “bridge” mosquito is required to serve as an intermediate vector of EEEV, responsible for transmission to humans or other uninfected mammals such as horses. Transmission between people or from horses does not occur, thus humans and horses are typically called "dead end" hosts.

Symptoms

Time from infected mosquito bite to onset of illness (incubation period) is about 4 to 10 days. Symptoms can range from mild flu-like illness to encephalitis, coma and death. Approximately a third of those who develop EEEV die while others typically have permanent neurologic damage.

Laboratory Testing

As with other arboviral infections, laboratories typically test serum or cerebrospinal fluid to detect virus-specific IgM and neutralizing antibodies.

Treatment

There is currently no human vaccine or specific anti-viral treatment for EEEV. Supportive care is recommended.

Statistics for VA

Human cases of EEEV in Virginia are somewhat rare. From 1975 through 2015, a total of six human cases have been reported. The most recent human case of EEEV was reported in 2012. Persons over age 50 and younger than age 15 seem to be at the greatest risk for developing severe disease.

For more information see Eastern Equine Encephalitis

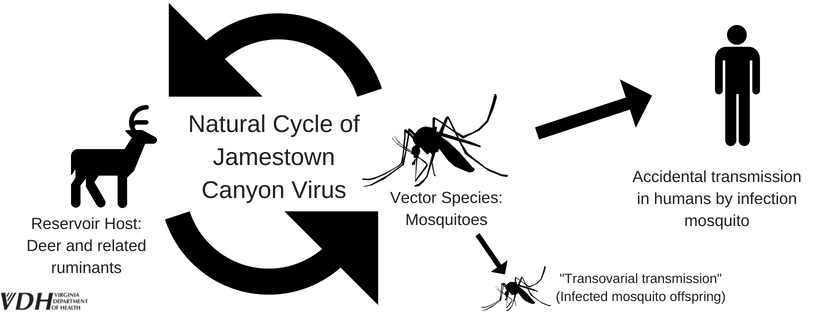

Jamestown Canyon virus (JCV) is primarily maintained by white-tailed deer and mosquitoes. Humans are considered "dead end" hosts because they do not develop enough virus in their bloodstream to reinfect mosquitoes and continue the transmission cycle.

Transmission

Several different mosquitoes can transmit JCV to humans meaning the risk for transmission is highest during mosquito season (May-October). Transmission between people does not occur.

Symptoms

Symptoms of JCV may present as fever, headache, chills, malaise, and nausea with more severe cases involving meningitis or encephalitis.

Laboratory Testing

As with other arboviral infections, laboratories typically test serum or cerebrospinal fluid to detect virus-specific IgM and neutralizing antibodies.

Treatment

There is currently no human vaccine or specific antiviral treatment for JCV. Supportive care is recommended.

Statistics for VA

JCV is thought to be under-diagnosed and may often go undetected or mistaken for a similar infection which belongs to the same California serogroup, La Crosse virus. Currently, there are no confirmed JCV cases in Virginia.

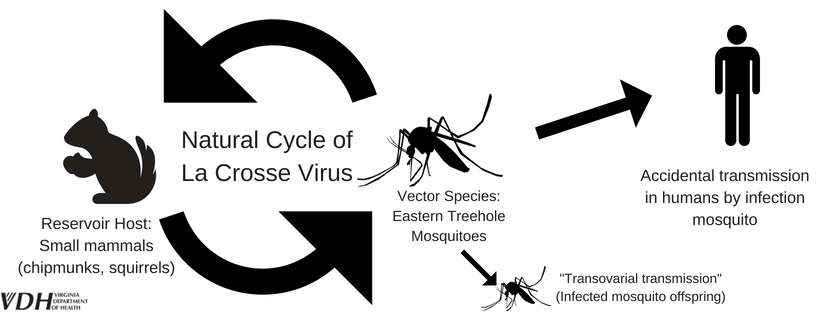

La Crosse Virus (LACV) is primarily maintained in a cycle between the Eastern tree-hole mosquito (Aedes triseriatus) and small mammals, such as chipmunks and squirrels. Humans are considered "dead end" hosts because they do not develop enough virus in their bloodstream to reinfect mosquitoes and continue the transmission cycle.

Transmission

Transmission to humans occur through the bite of an infected tree-hole (Aedes triseriatus) mosquito. These mosquitoes are day-time biters and lay their eggs in tree holes and water holding containers. Asian tiger mosquitoes can also serve as a potential vector of La Crosse Virus, LAC. Transmission between people does not occur.

Symptoms

Time from infected mosquito bite to onset of illness (incubation period) is about 5 to 15 days. Typically LAC presents as fever, headache, nausea, vomiting, and lethargy. Severe disease may occur in younger individuals and is characterized by seizures, coma, paralysis, and other neurological complications.

Laboratory Testing

As with other arboviral infections, laboratories typically test serum or cerebrospinal fluid to detect virus-specific IgM and neutralizing antibodies.

Treatment

There is currently no human vaccine or specific antiviral treatment for LACV. Supportive care is recommended.

Statistics for VA

In Virginia, there have been 20 reported cases of LACV between 2003-2014. On average, less than 2 cases are reported every year in Virginia. Most cases occur in children under 16 years of age.

For more information see La Crosse Encephalitis

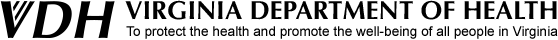

St. Louis encephalitis (SLEV) virus is maintained in a natural cycle between mosquitoes and birds. The virus must be amplified in birds such as sparrows, blue jays, pigeons, and robins before an infected mosquito is capable of transmitting the virus to people or other mammals. Humans are considered "dead end" hosts because they do not develop enough virus in their bloodstream to reinfect mosquitoes and continue the transmission cycle.

Transmission

Humans can acquire SLEV from bites of infected Culex mosquitoes. Transmission between people does not occur. These Culex vector mosquitoes can often be found near man-made water holding containers or polluted ditches, high in organic content.

Symptoms

Time from infected mosquito bite to onset of illness (incubation period) is about 4 to 15 days. However, most SLEV infections are asymptomatic but symptoms can range from nonspecific fatigue to severe meningitis or encephalitis. Elderly persons are at a higher risk for severe presentation of SLEV. CDC estimates that only 1% of SLEV infections are clinically apparent.

Laboratory Testing

As with other arboviral infections, laboratories typically test serum or cerebrospinal fluid to detect virus-specific IgM and neutralizing antibodies.

Treatment

There is currently no human vaccine or specific antiviral treatment for SLEV. Supportive care is recommended.

Statistics for VA

There have been no reported cases of SLEV infection in Virginia.

For more information see St. Louis Encephalitis

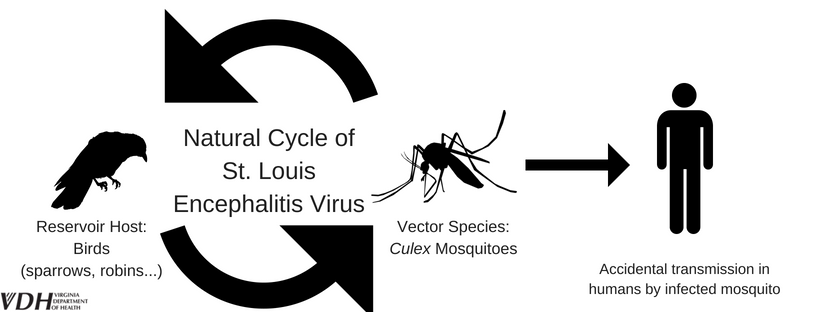

West Nile virus (WNV) typically cycles between mosquitoes, primarily of the Culex species, and birds. The virus must be amplified in birds such as crows, blue jays, pigeons, and robins before an infected mosquito can then transmit the virus to people or other mammals, such as horses. Humans and horses are considered "dead end" hosts because they do not develop enough virus in their bloodstream to reinfect mosquitoes and continue the transmission cycle.

Transmission

Humans can acquire WNV from bites of infected mosquitoes. Time from infected mosquito bite to onset of illness (incubation period) is about 2 to 14 days. Therefore, the highest risk of transmission is during the summer months when mosquitoes are most active. These Culex vector mosquitoes can often be found near man-made water holding containers or polluted ditches, rich with organic content. Transmission of WNV does not occur from person-to-person or animal-to-person contact.

Symptoms

About 80% of people infected with WNV will not develop any symptoms. About 20% of people will develop a fever and may experience symptoms such as headaches, body aches, joint aches, vomiting, diarrhea, or rash. An estimated 1 out of 150 infected people will develop a severe, neuroinvasive West Nile virus infection. This severe illness can cause fever, headache, stiff neck, disorientation or confusion, vision loss, seizures, paralysis, and even death. Individuals over 60 years of age are at an increased risk of developing a neuroinvasive infection and should take extra precautions to avoid mosquito bites.

Laboratory Testing

As with other arboviral infections, laboratories typically test serum or cerebrospinal fluid to detect virus-specific IgM and neutralizing antibodies.

Treatment

There is currently no human vaccine or specific antiviral treatment for WNV. Supportive care, such as pain medication and intravenous fluids, is recommended.

Statistics for VA

Virginia reported a total of 134 cases between 2003-2016 with an average of about 9 cases per year. The majority of cases are reported during late summer and early autumn (August-September).

For more information see West Nile Virus Infection

*Additional Note*

As of 2007, birds are no longer routinely tested for West Nile Virus infection. As groups or flocks of dead birds are much more likely to have died from an avian disease other than WNV, or from pesticide poisoning, dead groups or flocks of birds should be reported to the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries http://www.dgif.virginia.gov/ or the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (VDACS) Office of Pesticide Services (804-786-2042). For more information, please contact the Division of Environmental Epidemiology at 804-864-8182.

Imported/Travel Associated Mosquito-borne Diseases

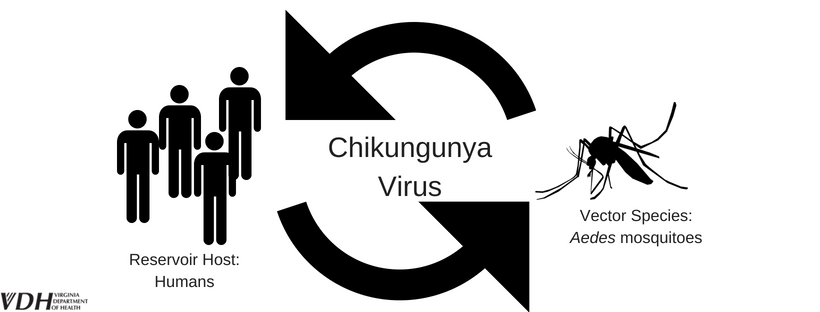

The Yellow fever (Aedes aegypti) and Asian tiger (Aedes albopictus) mosquitoes spread Chikungunya virus (CHICKV) to people. People with active infections can spread CHICKV to uninfected mosquitoes, continuing the transmission cycle.

Transmission

Mosquitoes become infected with CHIKV by feeding on other infected persons. Currently CHIKV is established across Africa, southern and southeastern Asia, Pacific Island nations, and in the Caribbean region of the Americas. There have been no known locally-acquired cases reported among Virginia residents, but there remains risk of infected travelers transmitting CHIKV to local Asian tiger mosquitoes, a very common Virginian mosquito.

Symptoms

Time from infected mosquito bite to onset of illness (incubation period) is about 1 to 12 days. Most people infected with CHIKV have a high fever that may be accompanied by joint pain or swelling in multiple joints, body aches, headache, nausea, back pain, and rash. The joint pain may become chronic and last several years after the acute illness, a distinguishing factor between Chikungunya and Dengue.

Laboratory Testing

Diagnosis of CHIKV takes into account travel to places where CHIKV is endemic, symptoms characteristic of CHIKV, and blood work that detects detect virus-specific IgM and neutralizing antibodies.

Treatment

There is currently no human vaccine or specific antiviral treatment for CHIKV. If you have traveled to a CHIKV endemic area and are experiencing symptoms as described, consult with your healthcare provider. Supportive care such as rest, hydration, and fever reducing medication like acetaminophen or paracetamol are recommended. If you do have CHIKV, avoid mosquito bites for the first week of your illness as this could further the spread of infection to others.

Statistics for VA

After CHIKV spread to the Caribbean region of the Americas in 2014, cases could be reported to CDC’s ArboNET, the national surveillance system for arthropod-borne diseases. In 2014, Virginia confirmed 59 reported cases of travel-associated CHIKV. CHIKV became a nationally reportable disease in 2015 when there were 24 reported cases, 6 reported cases in 2016 and 5 reported cases in 2017.

For more information see Chikungunya

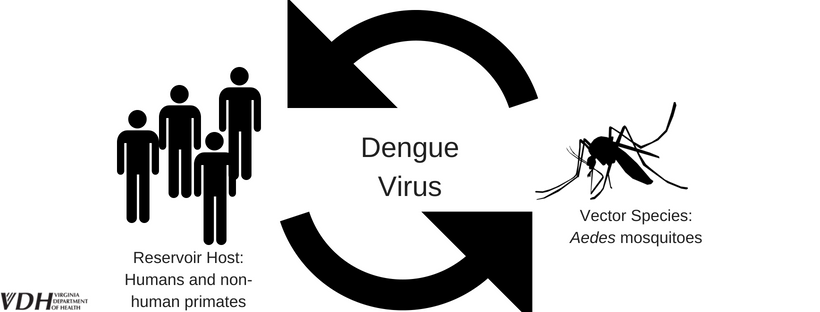

Dengue virus (DENV) is spread to people by the bite of the Yellow fever (Aedes aegypti) and Asian tiger (Aedes albopictus) mosquitoes. People with active infections can spread DENV to uninfected mosquitoes, continuing the transmission cycle.

Transmission

Mosquitoes become infected with DENV by feeding on other infected persons. DENV is not currently established in the USA and all reported Virginian cases have occurred from travelers returning from DEN endemic regions.

Symptoms

Time from infected mosquito bite to onset of illness (incubation period) is about 3 to 14 days. Dengue infection can cause different symptoms ranging from mild “flu-like” illness to high fever (104°F) with severe headaches, severe eye pain, muscle or joint pain, rash, or bleeding from the nose or gums. These symptoms could last 5-7 days and recovery is usually complete by 7-10 days, but fatigue and depression may last longer. Death from dengue fever is rare.

Dengue hemorrhagic fever may develop after a few days of illness and cause bruising and bleeding from multiple sites which may then lead to life-threatening Dengue shock syndrome. However, with good medical care, death occurs in less than 1% of cases.

Laboratory Testing

Diagnosis of DENV takes into account travel to places where DEN is endemic, symptoms characteristic of DENV, and blood work that detects detect virus-specific IgM and neutralizing antibodies

Treatment

There is no specific medication or treatment for dengue infection. If you have traveled to a DENV endemic area and are experiencing symptoms as described, consult with your healthcare provider. Supportive care such as rest, hydration, and fever reducing medication such as acetaminophen or paracetamol are recommended. If you do have DENV, avoid mosquito bites for the first week of your illness as this could further the spread of infection to others.

Statistics for VA

In Virginia, there are about 13 cases of DENV per year. All cases have been associated with an individual who got infected while traveling to a DENV endemic area.

For more information see Dengue Fever

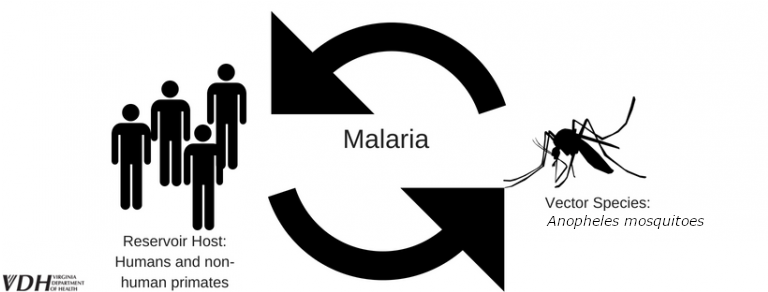

A parasite called Plasmodium infects certain types of mosquitoes and is the causative agent for Malaria. People with active infections can spread Malaria to mosquitoes, continuing the transmission cycle.

Transmission

The bite of an infected female Anopheles mosquito can transmit the parasite to a person which causes malaria. Malaria can also be passed from a mother to her unborn infant before or during delivery. Rarely, the malaria parasite is spread by blood transfusion or organ transplant.

Symptoms

Malaria symptoms may include high fever, chills, sweats, and headaches. Malaria may also cause anemia and jaundice. If left untreated, the infection can become extremely serious and lead to kidney failure, seizures, mental confusion, coma, and death.

Laboratory Testing

After determining likely infection based on travel history and clinical symptoms, malaria is typically confirmed by identification of the parasite by examining patient’s blood under a microscope.

Treatment

Antimalarial drugs exist and can be used to treat a confirmed infection. Preventative antimalarial drugs are also available and should be taken in advance and at the appropriate time (typically 4-6 weeks) before traveling to an area where malaria transmission occurs.

Statistics for VA

Each year, there are number of Malaria cases from individuals returning to Virginia after travel to a Malaria endemic country. On average, about 65 travel-related cases of Malaria are reported in Virginia each year.

For more information see Malaria

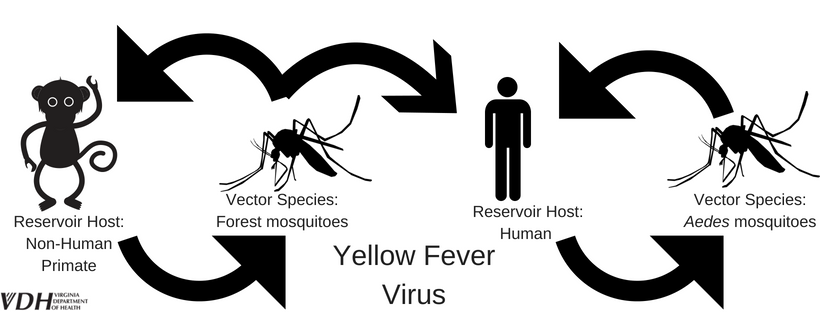

Yellow fever (YF) is caused by a virus spread by the bite of certain mosquitoes.

Transmission

This disease is spread to humans by the bite of an infected Aedes aegypti mosquito common in parts of Africa and South America. A mosquito that bites a person infected with yellow fever within the first five days of illness may then transmit the disease to other people it later bites. The disease is not spread person to person.

Symptoms

Yellow fever can cause fever, chills, severe headache, back pain, general body aches, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, and weakness. Most people improve after these initial symptoms occur. Some cases progress to more serious forms of illness, with symptoms including jaundice (yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes), high fever, bleeding (especially in the gastrointestinal tract), and eventually shock and failure of many organs.

Laboratory Testing

After confirming travel to areas with active Yellow fever transmission and relevant clinical symptoms, yellow fever infection may be diagnosed based on specific blood tests.

Treatment

The YF vaccine is recommended for persons aged 9 years and older that live in areas with active Yellow fever transmission, like Africa or South America, or for individuals traveling to these high-risk areas.

Statistics for VA

To date, there are no reported cases of Yellow fever in VA.

For more information see Yellow Fever

Zika is a virus mainly spread to people through the bite of an infected mosquito, specifically the Yellow fever mosquito (Aedes aegypti) or the Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus). People with active infections can spread ZIKV to mosquitoes, continuing the transmission cycle.

Transmission

While Zika is mainly spread through the bite of an infected mosquito, the virus may also be passed through unprotected sex, from a pregnant woman to her fetus, and through blood transfusion or organ transplant. If a mosquito bites an infected individual, the mosquito can become infected and continue to spread the virus. Individuals who travel to an area with risk of Zika, and who have not already been infected, can get Zika. Anyone who has unprotected sex with someone who lives in or travels to these places also is at risk for infection.

Symptoms

About 80% of people infected with Zika virus do not become sick. For the 20% of people who do become sick, they likely develop a fever, rash, joint pain, headache, red eyes, or muscle pain about 3-14 days after the bite of an infected mosquito. Zika has been shown likely linked to a neurological condition, Guillain-Barré Syndrome. Zika virus infection during pregnancy can cause microcephaly and other severe birth defects. For additional information on Zika virus and pregnancy in Virginia; visit our 'Zika and Pregnancy' site.

Laboratory Testing

If you have recently traveled to an area with active Zika transmission or had sexual relations with an individual that has recently traveled to an area with active Zika transmission and you have consistent clinical symptoms, a blood or urine test can be used to confirm Zika infection. For updated information, see VDH Zika Virus Testing Recommendations for Providers.

Treatment

There are no Zika specific treatments. If you believe you have Zika infection, see your healthcare provider. Supportive treatment such as rest, hydration, and fever reducing medication like acetaminophen are recommended.

Statistics for VA

2015 and 2016 represented an epidemic as Zika Virus spread through South America, Central America, North America, and the Caribbean. During this time, 119 cases (112 reported in 2016 and 7 reported in 2017) of Zika virus non-congenital disease (not in neonates) were reported. There has been a substantial decrease in the number of reported cases in Virginia and across the Americas. There have been no cases of reported Zika virus from local transmission of mosquitoes in Virginia. The Virginia Department of Health will continue to monitor the Zika situation closely and will provide additional information to Virginia clinicians and the public, as new information becomes available.

For more information see Zika

Other "Bug" Conditions

Of course everyone has seen, or at least heard of, mosquitoes and ticks, but you should also be aware of some of the other critters crawling around Virginia that may be a cause for concern. In this section we provide information on the not-so-common diseases spread by insects, arachnids, and bugs.

Quick Links

Other Vector-borne Diseases & Conditions

Chagas disease, or American trypanosomiasis, can be caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi carried by the “kissing bug” (triatomine bug).

Transmission:

Chagas disease primarily occurs in rural areas of Central and South America. The primary method of transmission to people is by contact with feces excreted by an infected blood-sucking triatomine bug as it feeds on the person. These bugs live in houses made of mud or straw and emerge at night to feed on the people as they sleep. They often bite people's faces, earning them the affectionate “kissing bug” name.

Chagas disease can also be passed from a pregnant women to her baby, through blood transfusion or organ transplantation, or consumption of food contaminated with infected bug feces.

Symptoms:

The acute phase of Chagas disease can involve symptoms such as fever, fatigue, body aches, headache, and rash. Unilateral eyelid swelling, called Romaña’s sign, is a unique symptom to Chagas disease. Acute phase infections often resolve in a few weeks but may be severe in young children or immunocompromised individuals.

The chronic phase of Chagas disease may appear decades after infection as cardiac or intestinal complications. These occur in about 30% of individuals with Chagas disease.

Laboratory Testing:

The parasite, T. cruzi, may be observed in a blood smear upon microscopic examination during the acute phase of illness. Diagnosis of chronic phase illness may involve epidemiological links and serologic testing.

Treatment:

Antiparasitic treatment is recommended for those affected by Chagas disease.

Statistics for VA:

There have been 9 cases of Chagas disease in the last decade in Virginia and almost all have been acquired out of the country.

For more information see Chagas

There are a few different types of Typhus fever including; scrub typhus spread by chiggers, murine typhus spread by fleas, and epidemic typhus spread by body lice are three types of bacterial typhus fever diseases.

Transmission:

Scrub typhus, caused by bacteria Orientia tsutsugamushi is transmitted to humans by the bite of infected chiggers. Rural areas of Southeast Asia, Indonesia, China, Japan, India, and Australia are the hotspots for most human infections.

Murine typhus, caused by bacteria Rickettsia typhi is transmitted to humans by the bite of infected fleas. In the United States, most cases have been associated with cat fleas in California, Hawaii, and Texas.

Epidemic typhus, caused by bacteria Rickettsia prowazekii is transmitted to humans by the bite of infected body lice. Rare cases occur in the United States, often in overcrowded areas such as prisons or refugee camps.

Symptoms:

Symptoms of scrub typhus are likely to begin within 10 days of being bitten by infected chiggers. These symptoms may include fever, headache, eschar (dark scab), and mental changes.

Symptoms of murine typhus are likely to begin within 2 weeks of contact with infected fleas. These symptoms may include fever, body aches, nausea, vomiting, cough, and a rash.

Symptoms of epidemic typhus are likely to begin within 2 weeks of contact with infected body lice. These symptoms may include fever, headache, rapid breathing, rash, and vomiting.

Laboratory Testing:

Be sure to mention travel or contact with pets and wild animals to your health care provider if you believe you could have typhus fever. Laboratory confirmation will involve a blood assay to detect typhus fever specific markers.

Treatment:

Antibiotics, typically doxycycline, are effective treatment for typhus fever infections.

Statistics for VA:

The most recent case of murine typhus in Virginia occurred in 2004. There is no record of any other typhus fever cases reported in Virginia.

For more information see Typhus

Plague is a disease that can affect humans and animals after the bite of a flea carrying the bacterium, Yersinia pestis.

Transmission:

Y. pestis is naturally maintained in a cycle between rodents and fleas in rural areas of western US. The low level of bacteria tends to cause no disruption to the natural ecology and has little effect on the rodent population. However, disruptions to the natural ecology (climate, rodent population levels, etc.) can force fleas to seek other animal or human hosts, thereby spreading plague.

Humans may become infected with bubonic plague by the bite of an infected flea or scratch from an infected animal, such as a cat. There is also a risk of transmission for those that are handling tissue or bodily fluids of a plague infected animal. This introduction of bacterium can cause septicemic plague which primarily affects hunters. Finally, plague can become aerosolized into infectious droplets and cause human-to-human or animal (often pets)-to-human transmission of pneumonic plague.

Symptoms:

Bubonic plague: Patients with bubonic plague may develop fever, headache, chills, and weakness or swollen lymph nodes (buboes) at the location of the bite from an infected flea.

Septicemic plague: Patients with septicemic plague may develop fever, chills, weakness, abdominal pain, shock, and internal bleeding. Skin may begin turning black on extremities.

Pneumonic plague: Patients with pneumonic plague may develop fever, headache, weakness, chest pain, cough, and blood or watery mucous. This may lead to respiratory failure.

Laboratory Testing:

The bacterium that causes plague may be detected and evaluated microscopically and by culture of blood samples or by other methods such as direct fluorescent antibody or PCR.

Treatment:

Antibiotic treatment with gentamicin and fluoroquinolones for 10-14 days will be administered upon diagnosis of plague. Early treatment by antibiotics increase likelihood of full recovery.

Statistics for VA:

In the United States, there are an average of 7 cases of plague each year with nearly all cases occurring in New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, California, Oregon, and Nevada. There has not been a case of plague in Virginia since the nineteenth century.

For more information see Plague