Last Updated: December 30, 2021

by Priya Pattath, PhD, MPH

Background

Recent studies suggest that pregnant women might be at an increased risk for severe illness associated with COVID-19. Historically, Black or African American and American Indian/Alaskan Native women have higher pregnancy-related morbidity and mortality rates compared to the rate for White women. Understanding the full spectrum of maternal and neonatal outcomes and health disparities associated with COVID-19 in pregnancy is important as studies have found that racial and ethnic minority pregnant women bear a disproportionate burden. Among risk factors, social determinants of health, like household crowding, occupations in essential services, and barriers to care may be potential underlying causes.

Hispanic and Black pregnant women appear to be disproportionately affected by COVID-19 infection during pregnancy. A seroprevalence study of pregnant women in Philadelphia found race/ethnicity differences in seroprevalence rates, with higher rates in Black and Latina women. 67% of the Black and Latina patients with COVID-19 had a preexisting condition such as chronic lung disease, diabetes, hypertension, or obesity, which may have contributed to increased vulnerability to COVID‐19 risk. Another retrospective study, conducted in Boston, reviewed data on COVID-19 and outcomes in the pregnant patient population. This study found that Latina women represented 48% of the cases and Black women represented 34% of the cases, 88% of those hospitalized were Black and Latina women. Obesity and Latina ethnicity represent risk factors for moderate and severe diseases. In patients with symptomatic COVID-19, intensive care unit admission, invasive ventilation, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and death were more likely in pregnant women.

Social determinants of health such as the social and physical environments in which people live affect the emergence, prevalence, and severity of COVID-19. Twenty-five percent of pregnant Latina women with COVID‐19 were experiencing housing insecurity. A Texas study reports that positive pregnant patients were more likely to be Latina and to have public insurance.

Recent studies have thus highlighted the racial and ethnic disparities in both risk for COVID-19 infection and disease severity among pregnant women. Similar disparities have been reported from Fairfax County, Virginia, where Latino residents make up 17% of the population but 59% of all coronavirus cases in August 2020. This indicates a need to address the potential risk factors in these populations in the Commonwealth of Virginia.

COVID-19 in Pregnant Women

The purpose of this study is to better identify disparities among pregnant women with COVID-19 across age groups, race/ethnicity, rural/urban, and pre-existing conditions, in Virginia and to determine the risk factors for hospitalization. Understanding the risk factors for COVID-19 infection in pregnant women can inform counselling, risk communication, and prioritize testing and vaccination strategies.

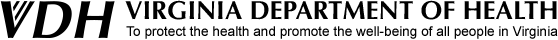

As of March 10, 2021, there were 3155 women who were COVID-19 positive and pregnant per the Virginia Electronic Disease Surveillance System (VEDSS). As seen in Table 1, most of this population was in the 20-34 years age group (74.8%), followed by the 35 years and over age group (20%). The majority of the pregnant women were Latinas and White, 38% and 32% respectively, while Black or African American women accounted for 19%. Race/ethnicity was not reported for 139 (4%) women. 29% of the women had a pre-existing condition like hypertension, diabetes, respiratory conditions among others. Pre-existing conditions were not reported for 13.4% of the pregnant women. Of the pregnant women with COVID-19, 216 (6.8%) required hospitalization. Data for hospitalization was missing for 4% of the sample.

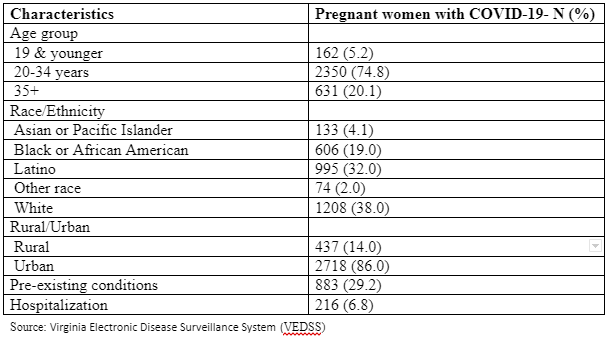

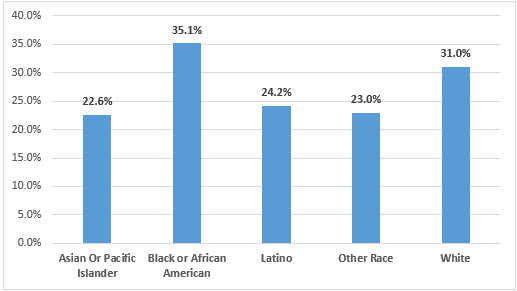

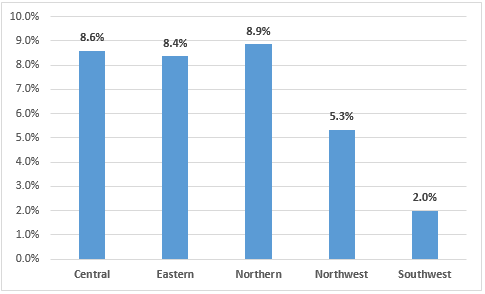

Of the total pregnant women with COVID-19, 883 (29.2%) reported having a pre-existing condition. Among the Black pregnant women, 35.1% reported having a pre-existing condition, among the White pregnant women 31% had a pre-existing condition, and 24.2% of Latino pregnant women had a pre-existing condition (Figure 1). Pregnant Latina (10.8%) and Other race women (10.8%) were hospitalized at a greater rate, followed by Black pregnant women (7.9%) than White or Asian women (3.2% and 6.8% respectively) (Figure 2). Pregnant women with COVID-19 were hospitalized a the highest rate in Northern Virginia (8.9%), followed by the Central region and the Eastern region (8.6% and 8.4% respectively) (Figure 3).

Methods

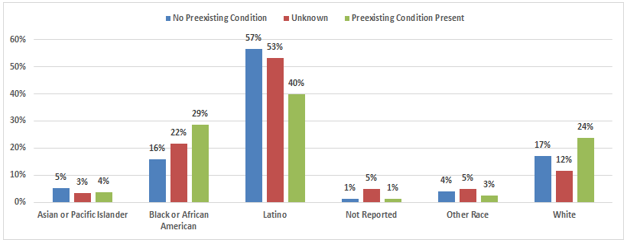

216 pregnant women with COVID-19 were hospitalized. Of the hospitalized pregnant women, 80 women had a preexisting condition, 40% were Latina, 29% were Black or African American, 24% were White, 4% were Asian or Pacific Islander, 3% were of Other race and 1% did not have race/ethnicity reported (Figure 4). Seventy-six pregnant women that were hospitalized did not have a preexisting condition. Of these, 57% were Latina, 17% were White, 16% were Black or African American, 5% were Asian or Pacific Islander, 4% were of Other race and 1% did not have race/ethnicity reported (Figure 4). Preexisting condition was not reported/unknown for 60 hospitalized pregnant women. Of these, 53% were Latina, 22% were Black or African American, 12% were White, 5% did not have race/ethnicity reported, and 5% and 3% were of Other race and Asian or Pacific Islander respectively (Figure 4).

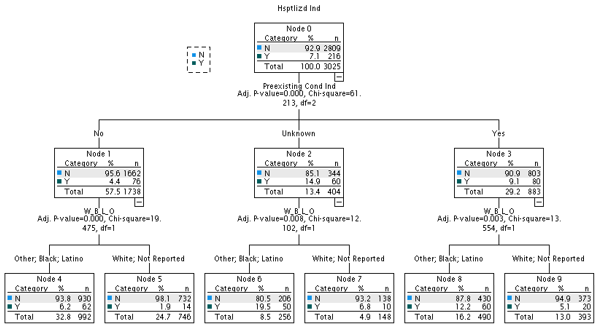

A Chi-square automatic interaction detector (CHAID) analysis was performed to explore the relationship between the variables- age group, rural or urban residency, race and ethnicity, and preexisting condition, and the outcome variable- hospitalization (Figure 5). CHAID analysis enables partition of the population into subgroups with different characteristics and estimation of hospitalization in each subgroup. This analysis creates all possible cross tabulations for each of the categorical predictor variables until the best outcome is achieved. CHAID analysis demonstrates a multilevel interaction among the risk factors through stepwise pathways.

Presence of preexisting conditions and interaction with demographic characteristics such as race/ethnicity, age groups, and rural or urban residency were examined in relation to the outcome variable, hospitalization. CHAID analysis was used to identify the strongest association between the predictors and the outcome variable. The most significant predictor of hospitalization was the presence of a preexisting condition (Figure 5). Of the total pregnant women, 29.2% had a preexisting condition reported, 57.5% of the pregnant women did not have a preexisting condition and presence of preexisting condition was unknown for 13.4% of the women. Pregnant women who had a preexisting condition (Node 3) had a significantly higher hospitalization rate (9.1%) than pregnant women who did not have a preexisting condition (4.4%) (Node 1).

However, it is observed that pregnant women for whom the presence of preexisting condition was unknown (Node 2), had the highest hospitalization rate (14.9%). This is because the second most important factor predicting hospitalization was race and ethnicity. In this group (Nodes 6 and 7), Latina, Black, and Other Race had a significantly higher hospitalization rate (19.5%) compared to White and missing race (6.8%).

In the group of pregnant women who had a preexisting condition, Latinas, Black and Other race women (Node 8) had a significantly higher hospitalization rate (12.2%) than White (5.1%) pregnant women (Node 9). For the group of pregnant women who did not report a preexisting condition, Latina, Black and Other Race (Node 4) had a significantly higher hospitalization rate (6.2%) than White women (1.9%) (Node 5).

Conclusion

As observed from the CHAID analysis (Figure 3), preexisting conditions, and race and ethnicity had a significant impact on hospitalization due to COVID-19 in pregnant women. Of the 883 pregnant women who had a preexisting condition, 80 (9.1%) had a hospitalization, while the groups of pregnant women who did not report a preexisting condition (N = 1738) and preexisting condition data was missing (N= 404), had a significantly higher hospitalization, 136 (19.3%), with the significant factor being of Latino origin. It is interesting to note that of the 60 pregnant women who were hospitalized and for whom the presence of preexisting condition was unknown, 50 women were Latina or Black.

The sub-group analysis thus confirms and supports previous findings that race and ethnicity appears to be an important predictor of hospitalizations. The findings suggest that the pregnant women with COVID-19 who had the highest probability of hospitalization were those that were of Latina or Black race/ethnicity or had a preexisting condition. These findings suggest that targeted interventions with focus on sub-population- Latinas, Black or African American could benefit from increased testing, vaccination and counselling strategies.

Limitations

There are several limitations that may have impacted the findings of this analysis such as incomplete and missing data for the predictor variables. Presence or absence of preexisting condition was not reported for 404 pregnant women in the data which may have contributed to increased vulnerability to COVID-19 and hospitalization. Majority of this group of pregnant women were Latina or White. This circumstance could lead to underestimation of preexisting conditions. The preexisting condition was self-reported and has not been verified with respective patient medical records. The self-reported diagnosis may differ from medical record diagnosis.

Occupation is an important variable that was incomplete in the VEDSS dataset and was missing for many cases and hence was not included as a predictor in this analysis. Many pregnant women of Latina origin may be working as essential workers. According to analysis by the Center of Economic and Policy Research, many working people in certain essential industries in Virginia are disproportionately women, immigrants, Black, and/or Latinx.

Social determinants of health such as overcrowding, income, insurance and education are important variables that need to be considered, as previous studies on pregnant women with COVID-19 have found that Latina women with COVID‐19 were experiencing housing insecurity.

Note: The “COVID-19 in Pregnant Women” section was updated on Dec. 30, 2021 to reflect rates, including charts.

Sources

Delahoy MJ, Whitaker M, O’Halloran A, et al. Characteristics and Maternal and Birth Outcomes of Hospitalized Pregnant Women with Laboratory-Confirmed COVID-19 — COVID-NET, 13 States, March 1–August 22, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1347–1354. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6938e1.htm

Ellington S, Strid P, Tong VT, et al. Characteristics of Women of Reproductive Age with Laboratory-Confirmed SARS-CoV-2 Infection by Pregnancy Status — United States, January 22–June 7, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:769–775. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6925a1

Flannery, D. D., Gouma, S., Dhudasia, M. B., Mukhopadhyay, S., Pfeifer, M. R., Woodford, E. C., Gerber, J. S., Arevalo, C. P., Bolton, M. J., Weirick, M. E., Goodwin, E. C., Anderson, E. M., Greenplate, A. R., Kim, J., Han, N., Pattekar, A., Dougherty, J., Kuthuru, O., Mathew, D., Baxter, A. E., … Hensley, S. E. (2020). SARS-CoV-2 Seroprevalence Among Parturient Women. medRxiv : the preprint server for health sciences, 2020.07.08.20149179. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.08.20149179

Olga Grechukhina, Victoria Greenberg, Lisbet S. Lundsberg, Uma Deshmukh, Jennifer Cate, Heather S. Lipkind, Katherine H. Campbell, Christian M. Pettker, Katherine S. Kohari, Uma M. Reddy, Coronavirus disease 2019 pregnancy outcomes in a racially and ethnically diverse population, American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology MFM, Volume 2, Issue 4, Supplement, 2020, 100246, ISSN 2589-9333.

Onwuzurike, C., Diouf, K., Meadows, A.R. and Nour, N.M. (2020), Racial and ethnic disparities in severity of COVID‐19 disease in pregnancy in the United States. Int J Gynecol Obstet, 151: 293-295. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13333

Emily E. Petersen et al., “Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Pregnancy-Related Deaths — United States, 2007–2016,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 68, no. 35 (September 2019): 762–765, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6835a3.htm

Pineles, B. L., Alamo, I. C., Farooq, N., Green, J., Blackwell, S. C., Sibai, B. M., & Parchem, J. G. (2020). Racial-ethnic disparities and pregnancy outcomes in SARS-CoV-2 infection in a universally-tested cohort in Houston, Texas. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology, 254, 329–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.09.012

Schmidt & Tan (2020). Pregnant Latina Women with COVID-19, Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2020/08/16/latina-pregnant-women-covid/

Mendes K, Goran, L. (2020). Profile of Essential Workers in Virginia During COVID-19, The Commonwealth Institute https://www.thecommonwealthinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Profile-of-Essential-Workers-in-Virginia-During-COVID-19.pdf

Stone (2020). https://www.forbes.com/sites/judystone/2020/07/22/bumpday-highlights-coronavirus-and-racial-disparities-in-pregnancy/?sh=328b17dc74c4

Virginia Department of Health, Virginia Electronic Disease Surveillance System (VEDSS), March, 2021.

WHO (2020) https://www.who.int/news/item/01-09-2020-new-research-helps-to-increase-understanding-of-the-impact-of-covid-19-for-pregnant-women-and-their-babies

Zambrano LD, Ellington S, Strid P, et al. Update: Characteristics of Symptomatic Women of Reproductive Age with Laboratory-Confirmed SARS-CoV-2 Infection by Pregnancy Status — United States, January 22–October 3, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1641–1647. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6944e3